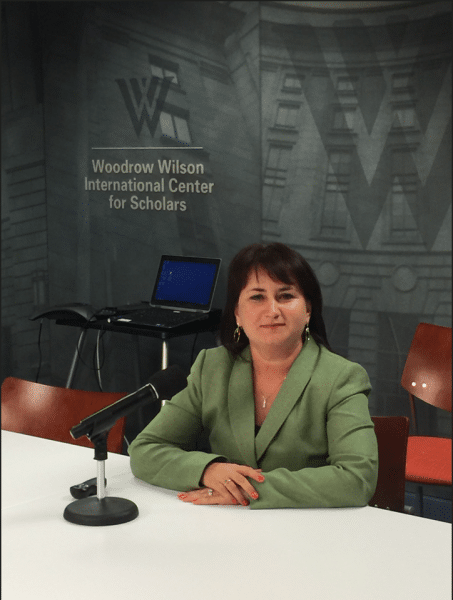

Valentyna Kharkhun

Professor of Ukrainian Literature and Journalism, Mykola Gogol State University (Nizhyn, Ukraine)

Throughout my career, my research has always overlapped with the subjects of Literature, Culture, and Memory Studies. I mainly work on the relationship between politics and culture, focusing on the following topics: ideology in Ukrainian modernist writings; the arts under Soviet rule; the socialist realist canon in Ukrainian and Russian Literatures; and the ideology of memory representations about communism within the museums of Central and Eastern European countries.

I generally focus on three main research areas: Vynnychenko Studies, Soviet Studies, and Memory Studies. I began researching Volodymyr Vynnychenko, a Ukrainian modernist writer and politician, in 1994 when I was a student at Nizhyn Mykola Gogol State University. In 2000, I defended my doctoral dissertation on Vynnychenko, and a year later, I organized the Vynnychenko Research Center within the Department of Ukrainian Literature and Journalism. During the last twenty years, I have organized five conferences on this subject, edited five volumes of Vynnychenko Reviews, and published my book, Volodymyr Vynnychenko’s Novel “Notes of the Snub-Nosed Mephistopheles”: Generics, Semantic Sphere and Imagology (2011).

Since 2004, I have also focused on Soviet Studies, mainly Ukrainian socialist realism. From 2005-2006, as a Fulbright scholar, I studied the Ukrainian ideological narratives of Soviet and diaspora literature at Penn State (Project title: “Communicative Strategies in Mainland and Emigrant Ukrainian Literature of Totalitarian Period: Author – Text – Reader”). In 2008, as a recipient of the J. Mianovsky Fund, and in 2009, as a recipient of the Queen Jadwiga Fund, I studied Polish socialist realism at Jagellonian University.

In 2008, I organized and led the Studia Sovietica Research Center within the Ukrainian Literature and Journalism Department at Nizhyn University in cooperation with the Taras Shevchenko Institute of Literature (the National Academy of Sciences). The center’s main task is to promote and coordinate individual and collective projects which analyze Soviet cultural politics, as well as provide a platform for studying the forms and methods of perception of the Soviet past. As the center’s leader, I organized three conferences, edited three volumes of Studia Sovietica, and supervised a doctoral dissertation and student research. Recently, I published a chapter, “Ukrainian Literature of the Late Soviet Period: The History of Three Generations of Poets,” in the collective monograph, The Literary Field under Communist Rule (2018).

In 2016, as a Kennan Institute fellow (Woodrow Wilson Center), I studied the museumification of the Soviet era in Ukraine and Russia. My previous broader research experience of working with several European cases of museumification of communism and this Kennan project resulted in an even more detailed study of Ukrainian memory politics. Even though there is a great collection of research on this topic, Ukrainian museums exhibiting the Soviet past have never until this time been the subject of substantial research. It is my desire that this research make a great contribution to academia, introducing Ukrainian perceptions of the Soviet past from museums, and incorporating it into the context of expanded research of Central and Eastern European memory politics.

Currently, I am working on a book project, Multi-Faceted Memory: Exhibiting the Soviet Era in Ukrainian Museums. I am studying how narratives about the Soviet era exemplify and mirror the Ukrainian case of post-Soviet political, economic, and cultural transition and how those narratives illuminate new approaches to dealing with the contested past while (re)constructing a national identity. This research complements the broad context of how other Eastern European countries have memorialized the communist past to highlight the peculiarities of the Ukrainian experience with “memory in transition”–by distinguishing the uniqueness of Ukrainian narratives of the Soviet past and accenting any similarities to the same narratives created elsewhere in Eastern Europe. Ultimately, this project will detail how the Ukrainian “memory in transition” fits into the European map of contemporary memory projects by discussing Ukraine’s contributions to the cosmopolitan memory of communism and why these memories are important to European ontological security.

Since February 24, 2022, like everyone else in Ukraine, scholars have faced a new reality and have accepted new roles. Although many university teachers have remained in their home cities and are performing their regular duties by teaching and emotionally supporting their students, many other scholars are now displaced; however, thanks to a variety of scholar-at-risk programs, they have temporarily joined Western universities and research institutions. Some colleagues are embracing totally new roles. They have decided to be volunteers, providing the Ukrainian army with military equipment, while others have enlisted with the Ukrainian army or territorial defense. In whatever roles we now find ourselves in, the biggest and the most dreadful challenge is the lack of normality which is affecting our ability to perform our pre-war routines–conducting research. Even colleagues who are not on the front line but in relatively safe places are having trouble with their research plans because of devastating stress, emotional unrest, and uncertainty. Despite these tremendously difficult times, I believe that Ukrainian scholars are still quite united in focusing on their main task: the defense of Ukraine, spreading knowledge about the Ukrainian mission in this war, and making Ukraine more visible on the world political and cultural maps. In other words, more than ever, Ukrainian scholars are becoming “cultural agents” in the fight for Ukraine’s liberation. That is why many of us paused writing academic books and prioritized other activities which can engage a larger audience: we are now writing blogs, presenting lectures, giving interviews, and participating in conferences. For example, for the first time in my career, I started to write blogs about the war in English and Ukrainian. Using my expertise, I am endeavoring to explain to readers how different attitudes to the Soviet past in Ukraine and Russia have contributed to this war and make clear what Ukraine is fighting for. I believe practical use of our research experience best promotes knowledge about Ukraine and the ongoing war.

I fled Ukraine in March because the war affected Nizhyn, my home city in the Chernihiv region. I recently arrived in the US and am now living in the DC area with my husband. It has taken me almost two months to overcome much of the stress and trauma. My American colleagues (and I am thankful for them) have engaged me in numerous research activities, and this helps to provide me with a feeling of “normality” as well as an understanding that my research is still needed and that I can spread knowledge about Ukrainian culture and memory politics.

As for my previous research, I might need to reconsider my book project, especially since many of the museums I was planning to analyze are in warzones. Last year I conducted substantial fieldwork in Western and Central Ukraine and had planned to do the same in Eastern Ukraine starting in the spring. The war completely changed my plans. It is no longer clear when I will be able to continue my field study, so this is pushing me to make difficult decisions about rearranging my primary research projects.

On the other side of the coin, surprisingly, the ongoing war and memory politics provides me with exclusive data for my research on the attitudes about Soviet times. I believe that analyzing contemporary struggles for the Soviet past as an integral part of the Russo-Ukrainian war will strengthen my arguments about the Ukrainian specificity in dealing with the contested past.

I believe that everybody is doing everything they possibly can, and I deeply appreciate the help my Ukrainian colleagues and I have received from our Western colleagues. My only wish would be that we might continue these opportunities for collaboration in our future collective projects to make Ukraine more visible and attractive for research.

It is difficult, if not impossible, to predict how the war will change the academic landscape in Ukraine. However, thinking about possible changes, I would consider two issues. First is the large influence of the scholar-at-risk programs. As so many Ukrainian scholars are being supported by different research institutions and are receiving a chance to spend substantial time within Western academia, they can bring the experience gained in teaching, research, academic ethics, and freedom into Ukrainian academia. I believe that these experiences can definitely contribute to the implementation of very needed reforms in Ukrainian academia and will help promote continued and successful cooperation of the Ukrainian research community with Western colleagues. In addition, this large presence of Ukrainian scholars in Western academia will contribute to the field by promoting Ukrainian Studies and make Ukrainian research more visible within Slavic Studies programs.

The second issue I would like to discuss is revisiting or decolonizing Slavic Studies, both in the Ukrainian context and especially within Western academia. Russian Studies as a program largely dominates and overshadows Slavic Studies or Eastern European Studies, marginalizing other countries from the region. Now might be a good time to understand and accept that by prioritizing Russia within Slavic Studies, we are merely contributing to the myth of Russian exclusiveness and “Great Russian Culture,” which is being used in Kremlin propaganda to justify the war in Ukraine. Although I would like to note that this does not mean “canceling” Russian culture, it means diminishing its devastating dominance as a “privileged” object in research and university curricula. Now is the time to listen to the previously silenced voices from the region, not only from Ukraine but also from Poland, Slovenia, Slovakia, Romania, etc. Moreover, Slavic and Eastern European Studies is not exclusively about Russia but also about a large number of other countries, each with unique histories and cultures. Therefore, I believe it is becoming necessary to reconsider and modernize the field by rearranging the “dominance” and “prevalence” of Russian Studies from within Slavic Studies.